James Joyce - Ulyssses

* The quoted dash ‘-’ (pronounced as ‘libremes to’) serves as a referential signifier for the link between two libremes (smallest unit of intertextuality).

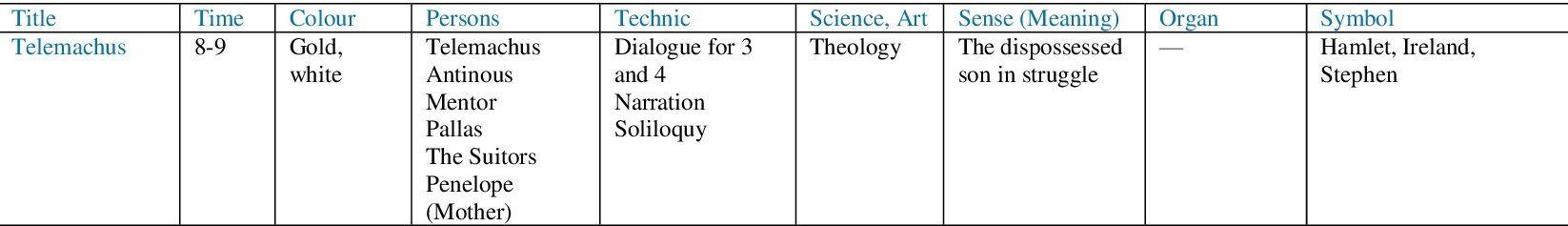

Libros: Varies from subjects of Theology, History, Philology, Economics, Botany/Chemistry, Religion, Rhetoric, Architecture, Literature, Mechanics, Music, Politics, Medicine, Magic, Navigation and Science (Linnati Schema). Tells a story which aims to pull the reader into the orbit of the protagonist’s hyperlibreal and literary consciousness, which conflates .

I. Telemachus

Summary: The chapter of Telemachus in James Joyce's Ulysses serves as the opening of the novel, introducing Stephen Dedalus, who lives in the Martello Tower with his friend, Buck Mulligan, and an Englishman named Haines. Set on June 16, 1904, it captures Stephen's strained relationship with Mulligan, his mourning over his mother's recent death, and his sense of alienation and bitterness. The chapter ends with Stephen refusing to return to the tower that night, signaling his desire to break away from his current life.

from the Linnati Schema

Litterolibreme:

I. Homer, The Odyssey

i. ‘If he stays on here I am off’ ‘-’ Telemachus attempts to get rid of the suitors, and fails.

ii. He peered sideways up and gave a long low whistle of call, then paused awhile in rapt attention, his even white teeth glistening here and there with gold points. Chrysostomos. Two strong shrill whistles answered through the calm. ‘-’ ‘Then Zeus, whose voice resounds around the world, sent down two eagles from the mountain peak. At first they hovered on the breath of wind, close by each other, balanced on their wings. Reaching the noisy middle of the road, they wheeled and whirred and flapped their mighty wings, swooping at each man's head with eyes like death, Then to the right they flew, across the town. Everyone was astonished at the sight.’

iii. “I am off” ‘—’ Stephen's soon-abandoned ultimatum to Mulligan, "If he stays on here I am off," echoes events at the beginning of the Odyssey. Telemachus attempts to get rid of the suitors, and fails. Athena, in her disguise as Mentor, advises him to overcome his impotent dissatisfaction and take action, by leaving Ithaca to go looking for news of his father. Similarly, Stephen feels excluded and demeaned by Mulligan's alliance with Haines, and resolves to leave.

Although Stephen leaves the tower at the end of this episode less dramatically than Telemachus or Joyce (he heads off to a morning of teaching at Mr. Deasy’s private boys’ school), he resolves not to return at night. He avoids a planned meeting with Mulligan and Haines at The Ship—a narrative echo of Telemachus’ evasion of the ambush at sea planned by Antinous and his companions. And when Mulligan catches up with him in Scylla and Charybdis, he thinks, “Hast thou found me, O mine enemy?”

II. Shakespeare, Hamlet; Homer, The Odyssey,

i. ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead […] He faced about and blessed gravely thrice the tower […] He pointed his finger in friendly jest and went over to the parapet’ ‘-’ (A symbolic bilocation of Homer’s Ithacan palace, and the Elsinore castle in the opening scene of Hamlet)

ii. He peered sideways up and gave a long low whistle of call, then paused awhile in rapt attention, his even white teeth glistening here and there with gold points. Chrysostomos. Two strong shrill whistles answered through the calm. ‘-’ ‘Then Zeus, whose voice resounds around the world, sent down two eagles from the mountain peak. At first they hovered on the breath of wind, close by each other, balanced on their wings. Reaching the noisy middle of the road, they wheeled and whirred and flapped their mighty wings, swooping at each man's head with eyes like death, Then to the right they flew, across the town. Everyone was astonished at the sight.’ Odyssey, Homer, 147-56, trans. Wilson.

III. Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist.

i. ‘O, my name for you is the best: Kinch, the knife-blade.’ ‘-’ 'The kinchins, my dear,' said Fagin, 'is the young children that's sent on errands by their mothers, with sixpences and shillings; and the lay is just to take their money away––they've always got it ready in their hands––then knock 'em into the kennel, and walk off very slow, as if there were nothing else the matter but a child fallen down and hurt itself. Ha! ha! ha!'

IV. Ulick O’Connor, Gogorty

i. ‘You saved men from drowning’)

V. The Holy Bible

1. Mock Mass scene

I pinched it out of the skivvy's room, Buck Mulligan said. It does her all right. The aunt always keeps plainlooking servants for Malachi. ‘Lead him not into temptation.’ And her name is Ursula. ‘—’ Pater Nestor

VI. Anabasis, Xenopohon

Thalatta! Thalatta! ‘—’ The ancient Greek that Mulligan declaims in Telemachus, “Thalatta! Thalatta!" comes from Xenophon's Anabasis, which he again quotes from in Oxen of the Sun. The Greek army whose story this work tells escaped near-certain death in Asia Minor and reached the shore of the Black Sea, expressing its relief and exultation in the cry, "The sea! The sea!"

VII. Oscar Wilde, Shakespeare

The rage of Caliban at not seeing his face in a mirror, he said. If Wilde were only alive to see you! (*metalepsis) ‘—’ The nineteenth century dislike of realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass, Oscar Wilde - The Picture of Dorian Gray “—” [Caliban is described as] Abhorrèd slave, Which any print of goodness wilt not take, Being capable of all ill!, Shakespeare, The Tempest

It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked lookingglass of a servant. (Mirrors) ‘—’ M. H. Abrams showed in a classic study that mirrors have long been regarded as symbols of art conceived classically as a faithful mimetic representation of external reality. Stephen's characterization of the mirror seems to suggest that faithful representation of reality is difficult within the confines of colonial subjection. However, In James Joyce's Ulysses: A Study (1930), Stuart Gilbert noted an additional context for the image of a “cracked looking glass” that may complicate or even refute the foregoing reading. In The Decay of Lying (1889), Oscar Wilde uses the phrase to object to the notion that art mirrors external reality. Wilde espoused the Romantic belief in individual genius—the view that Abrams characterizes as a "lamp." In this view, the genius of the artist is more valuable than what most human beings regard as reality. The fact that Stephen repeats Wilde's phrase verbatim, and the fact that Mulligan has just invoked another work by the same author, may recommend this anti-mimetic reading of the sentence.

Poeticolibreme

I. W.B. Yeats Who Goes With Fergus

i. 'Love's bitter mystery" ‘-’

II. The Triumph of Man, Algernon Charles Swinburne -

'Great Sweet Mother' I will go back to the great sweet mother, Mother and lover of men, the sea.

III. Robert Burns (1759-96) On a Louse

“As he and others see me” (regarding himself in the mirror held up by Mulligan) ‘—’ O wad some Power the giftie gie us / To see oursels as ithers see us!

Theolibreme

And her name is Ursula. ‘—’ Ursula was a 3rd century Christian martyr passionately devoted to virginity.

Theomythicolibreme

i. His even white teeth glistening here and there with gold points. Chrysostomos. ‘—’ The Greek word "Chrysostomos" in the tenth paragraph of Telemachus compounds Chrysos (gold) and stoma (mouth). Several orators of antiquity acquired this epithet "golden-mouthed," notably St. John Chrysostomos (ca. 349-407)

ii. Paralibreme: 'Chrysostomos' (as deployment of interior monologue) -Édouard Dujardin 'Les lauriers

iii. Paralibreme: 'interior monologue' (a narrative term popularized by Joyce to describe Dujardin's invention) - Paul Bourgeiv. — The mockery of it! he said gaily. Your absurd name, an ancient Greek! ‘—’ Daidalos (Latin Daedalus) means "cunning workman," "fine craftsman," or "fabulous artificer" (this last phrase comes from A Portrait of the Artist, and Jovce repeats it Sculla and Chambdis). Dedalus was a legendary artisan whose exploits were narrated by ancient poets from Homer to Ovid.

Daedalus was famed for three particular creations, one of which comments upon Stephen’s son-like combination of potential and immaturity. Ovid tells the story of how the craftsman, trapped on Crete by King Minos, fashioned two pairs of artificial wings to escape his island prison—one for himself and one for his son Icarus. He warned Icarus not to fly too high, lest the heat of the sun melt the wax attaching the feathers to the artificial wings. Carried away with the joy of flight, Icarus forgot his father’s warning, flew too close to the sun, and fell to his death in the sea.Historicolibreme: Stephans means crown or wreath, and carries associations with the garlands that were draped over the necks of bulls marked for sacrifice. The first Christian martvr was named St. Stephen, probablv because of this association with sacrifice.

v. My name is absurd too: Malachi Mulligan, two dactyls. But it has a Hellenic ring, hasn't it? ‘—’ Noting that both names are "dactyls" confirms the typical Irish pronunciation of the first one: MAL-uh-kee, which rhymes rhythmically with the last name just as Oliver rhymes with Gogarty. The dactyls also insinuate one more hint that Joyce's novel is somehow retelling the story of the Odyssey, because Homer's long poem was composed in dactylic hexameter: prosodic lines of six DUH-duh-duh feet.

vi. “Someone killed her” ‘—’ In Scylla and Charybdis he refers to a deity “whom the most Roman of catholics call dio boia, hangman god,” which Gifford notes is "a common Roman expression for the force that frustrates human hopes and destinies." This god, a redhanded "butcher," makes many appearances in the Hebrew Bible.

Aestheticolibreme

i. '[Mulligan's plump shadowed face' (as deployment of interior monologue) "' Like Joyce himself at the same age, Stephen has recently returned from a self-imposed exile in Paris where he had little to eat. (Joyce complained often and pitifully to his mother, who sent him money orders when she could.) From this perspective, Mulligan's "Plump" appearance evokes Stephen's lean and hungry resentment of his well-fed benefactor.

ii. The aunt thinks you killed your mother ‘—’ You could have knelt down, damn it, Kinch, when your dying mother asked you, Buck Mulligan said. I'm hyperborean as much as you. But to think of your mother begging you with her last breath to kneel down and pray for her. And you refused. There is something sinister in you (Telemachus, Ulysses, Joyce);

'Pentiti, cangia vita...Pentiti, scellerato...Pentiti' ‘No, no, ch'io non me pento...No, vecchio infatuato...No!' (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Don Giovanni);

Autobiographicolibreme

i. ‘Mulligan's plump shadowed face’ (as deployment of interior monologue) ‘—’ Like Joyce himself at the same age, Stephen has recently returned from a self-imposed exile in Paris where he had little to eat. (Joyce complained often and pitifully to his mother, who sent him money orders when she could.) From this perspective, Mulligan's "Plump" appearance evokes Stephen's lean and hungry resentment of his well-fed benefactor.

ii. ‘How long is Haines going to stay in this tower?’ ' ‘—’ Buck Mulligan in Ulysses by James Joyce is based on Oliver St. John Gogarty, a real-life friend of Joyce. Gogarty was known for being a witty, outspoken, and larger-than-life personality, much like Mulligan in the novel. He was also a medical student, as Mulligan is, and had a sharp sense of humor, often mocking people and institutions, which comes through in Mulligan's irreverent attitude. Joyce and Gogarty had a complicated friendship—Gogarty could be charming but also offensive, much like Buck Mulligan's relationship with Stephen Dedalus.

Haines, on the other hand, is based on Samuel Chenevix Trench, another real person from Joyce's circle. Trench was an Englishman who shared the intellectual curiosity and eccentric interests that we see in Haines. In Ulysses, Haines is fascinated by Irish culture but also somewhat oblivious to the deeper realities of it, reflecting the way Trench, as an outsider, may have been perceived by Joyce. Trench, like Haines, had a somewhat detached, scholarly interest in Ireland and its language, but lacked a true understanding of the country's more complex dynamics.

iii. “He was raving all night about a black panther, Stephen said. Where is his guncase?... Out here in the dark with a man I don't know raving and moaning to himself about shooting a black panther." ‘—’ In real life, something similar happened to Joyce. He stayed with Oliver St. John Gogarty (the inspiration for Buck Mulligan) and Samuel Chenevix Trench (the model for Haines) in the Martello Tower in Dublin. One night, Trench, possibly suffering from a mental episode, became paranoid and believed he saw a black panther. He started firing shots inside the small stone room where they were staying. Bullets flew around, and Joyce, terrified by the gunfire, fled the tower. This frightening incident contributed to Joyce's decision to leave Dublin and was later fictionalized in Ulysses with Stephen’s discomfort around Haines.

iv. “You saved men from drowning” ‘—’ Gogarty did in fact save men from drowning, snatching people from the Liffey at least four times between 1898 and 1901, and his aquatic heroism outlived his twenties. In November 1922, the commander of an IRA faction that opposed the Treaty between Ireland and Great Britain authorized the killing of Irish Free State Senators, of whom Gogarty was one. Two months later he was kidnapped by IRA soldiers and held in a house near Chapelizod. Aware that he might soon be executed, he feigned diarrhea, was led out into the garden, broke free, jumped into the Liffey, and swam to freedom in Phoenix Park. Ulick O’Connor's authorized, and valuable, biography of Gogarty details these events beginning on p. 194.

Intralibremes:

i. Daidalos (Latin Daedalus) means “cunning workman,” “fine craftsman,” or “fabulous artificer” ‘-’ This last phrase comes from A Portrait of the Artist, and Joyce repeats it Scylla and Charybdis.

ii. A Portrait opens with an epigraph from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: et ignotas animum dimittit in artes, “and he applies his mind to unknown arts." It concludes with a secular prayer: “Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.” Both are references to Daedalus. The Portrait, then, presents Stephen as potentially an artificer comparable to the legendary Greek craftsman, his spiritual father.

iii. If Stephen is more like the son than the father, then his efforts to fly will be marked by disastrous failure more than triumph. Both A Portrait and Ulysses confirm this expectation. The earlier novel establishes a recurring pattern of triumph followed by failure, flight followed by descent. It ends on a high note, with Stephen resolving to “fly by” the nets thrown at the soul in Ireland “to hold it back from flight.” He looks at birds in flight and thinks “of the hawklike man whose name he bore soaring out of captivity on osierwoven wings.” He prepares to go “Away! Away!” (to Paris), thinking of kindred souls “shaking the wings of their exultant and terrible youth.” But Ulysses finds him back in Dublin, picking seaweed off his broken wings. He is unachieved and unrecognized as an artist, unloved and unwed in a book whose subject is sexual love, and soon to be unhoused and unemployed.iv. In Proteus Stephen imagines his father Simon learning that he has been hanging out in the run-down house of his Aunt Sally and responding with contemptuous derision: "Couldn't he fly a bit higher than that, eh?" In Scylla and Charybdis he thinks, “Fabulous artificer. The hawklike man. You flew. Whereto? Newhaven-Dieppe, steerage passenger. Paris and back. Lapwing. Icarus. Pater, ait. Seabedabbled, fallen, weltering. Lapwing you are. Lapwing be.” The cry of Pater (“Father”) identifies him with Daedalus’ much-loved son. “Lapwing” identifies him with a low-flying, non-soaring bird that also figures in the mythology of Daedalus

- Daedalus’ first work involved cattle, in what Oxen of the Sun calls the fable "of the Minotaur which the genius of the elegant Latin poet has handed down to us in the pages of his Metamorphoses." The artificer helped Pasiphae, the queen of Crete, to satisfy her desire for a particularly good-looking bull by constructing a hollow artificial cow that allowed the bull’s penis to enter both it and her. The fruit of this copulation was the Minotaur. Bulls were central to Minoan civilization; it worshiped them, and young men and women performed a spectacular ritual of vaulting over them by gripping their horns. Minos himself sprang from the union of Europa with the white bull in which Zeus visited her, and Poseidon inflicted Pasiphae’s lust upon her as punishment for Minos’ refusal to sacrifice a particularly magnificent sea-born bull to the god.v. Joyce alludes to the racy story of Pasiphae in Scylla and Charybdis, when Stephen’s list of sexual taboos includes “queens with prize bulls,” and in Circe, when he thinks again of the woman “for whose lust my grandoldgrossfather made the first confessionbox.” He may also be alluding to it obliquely in Oxen of the Sun, when bulls and sex again get mixed up with religion and confession: “maid, wife, abbess, and widow to this day affirm that they would rather any time of the month whisper in his ear in the dark of a cowhouse or get a lick on the nape from his long holy tongue than lie with the finest strapping young ravisher in the four fields of all Ireland . . . and as soon as his belly was full he would rear up on his hind quarters to show their ladyships a mystery and roar and bellow out of him in bulls’ language and they all after him.”

vi. These particular passages may only characterize Stephen by contrast (as someone who rejected the priesthood), but he is repeatedly associated with cattle in general and bulls in particular, beginning with the first sentence of A Portrait of the Artist: “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo.” Later in Portrait the cries of some swimming boys—“Come along, Dedalus! Bous Stephanoumenos! Bous Stephaneforos! . . . Stephanos Dedalos! Bous Stephanoumenos! Bous Stephaneforos!”—make him briefly a Greek bull, ox, or cow (Bous is gender-indeterminate). His agreement in Nestor to carry Mr Deasy’s letter to two newspaper editors makes him think, “Mulligan will dub me a new name: the bullockbefriending bard”—a phrase which floats through his mind in two later episodes. In Oxen, the two motifs come together: “I, Bous Stephanoumenos, bullockbefriending bard, am lord and giver of their life. He encircled his gadding hair with a coronal of vineleaves, smiling at Vincent. That answer and those leaves, Vincent said to him, will adorn you more fitly when something more, and greatly more than a capful of light odes can call your genius father.”

vii. As Stuart Curran has observed in "'Bous Stephanoumenos': Joyce's Sacred Cow," JJQ 6:2 (Winter 1969): 163-70, Stephen's friends in Portrait seem to be ridiculing him as "something of a blockhead who refuses to join their fun," but the verb stephanon means "to encircle or wreathe," and the noun stephanos means "wreath or crown," so his very name identifies Stephen as "a hero, a youth singled out from the mass of his countrymen" (163). He and Vincent play upon the notion that great poets are crowned with laurel wreaths—with Vincent observing that he has not yet deserved such accolades, having written only a handful of short lyrics. But the root sense of his name also identifies him as a sacrificial victim, since the garlanded oxen of ancient Greece were marked for slaughter, and (as Curran also observes) the Greek passive verb stephanomai can mean “to be prepared for sacrifice” (167). Thus the “ancient Greek” significance of stephanos forms an intelligible link to the other figure who is usually regarded as a basis of the name Joyce chose for his autobiographical persona: St. Stephen Protomartyr, the first of the Christian martyrs.

viii. “You saved men from drowning” ‘—’ In Telemachus Stephen says to Mulligan, "You saved men from drowning. I'm not a hero, however." In Eumaeus Bloom thinks of Mulligan's "rescue of that man from certain drowning by artificial respiration and what they call first aid at Skerries, or Malahide was it?" Drawing on a real-life difference between Joyce and Oliver Gogarty, the novel returns repeatedly to the theme of saving another life, beginning with Stephen's meditations in Proteus on whether he could ever be capable of such a thing: "He saved men from drowning and you shake at a cur's yelping.... Would you do what he did? A boat would be near, a lifebuoy. Natürlich, put there for you. Would you or would you not?"

Ulysses continues to follow the thread of aquatic heroism, but subsequent instances are tinged with sardonic irony. In Hades we learn that the son of Reuben J. Dodd jumped into the Liffey, probably in an attempt at suicide, and was hooked out by a boatman. Dodd rewarded the rescuer “like a hero,” with the un-princely sum of a florin (two shillings). Hearing the story, Simon Dedalus remarks “drily” that it was “One and eightpence too much.”In Wandering Rocks Lenehan alludes to the story of Tom Rochford going down into a sewer to rescue a man overcome by gas. “’He’s a hero,’ he said simply. . . . ‘The act of a hero.’” In this instance, however, life complicates the simplicity of art. Robert Martin Adams describes how twelve men in succession went down the manhole, one after another becoming overcome by the methane and requiring a new rescuer to enter the fray (Surface and Symbol, 92-93). Tom Rochford was merely the third in this series of comically futile heroic actors, but Joyce knew and liked Rochford and decided to elevate his importance.

In Circe, the importance is inflated to absurd proportions, as Rochford, Christ-like, jumps in to save the dead (Paddy Dignam) rather than the dying. Paddy Dignam, who has become a dog, worms his way down through a hole in the ground, followed by “an obese grandfather rat” like the tomb-diving one that Bloom sees in Hades. Dignam’s voice is heard “baying under ground.” Tom Rochford, following close behind, pauses to orate: “(A hand to his breastbone, bows) Reuben J. A florin I find him. (He fixes the manhole with a resolute stare) My turn now on. Follow me up to Carlow. (He executes a daredevil salmon leap in the air and is engulfed in the coalhole. . . .)”

ix. “I’m not a hero” ‘—’ In its immediate narrative context in Telemachus, “I’m not a hero” refers to Stephen’s morbid fear of water and to his nonaggressiveness. But it also constitutes a pointed reference to his original fictional name. When Joyce stayed with Gogarty in the tower he was working on a book called Stephen Hero, a long and eternally unfinished autobiographical novel whose materials Joyce eventually reworked into A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The title does not imply straightforward glorification of the protagonist. Ellmann speculates that when Joyce sought a new one, it was “because he felt the first title might imply a more sardonic view of his hero than he intended” (193).

As he changed Stephen Hero into the Stephen Dedalus of A Portrait and then the Stephen Dedalus of Ulysses, he nevertheless subjected him to harsher and harsher treatment. At the end of the first chapter of A Portrait, Stephen is hailed as a hero by the other boys at Clongowes Wood College, and carried in triumph like a Roman conqueror, because he went to the rector to protest an unjust beating at the hands of a priest whom the boys all fear. But he learns later that the incident was a source of amusement to the rector. After that point he cannot take leadership seriously, even when other boys look up to him or when the priests admire his piety. In Ulysses, the question about Stephen seems to be not whether or not he is a hero, but whether or not he is a total failure.

In a letter written to his brother Stanislaus from Pola in 1905, when he was still busily working on Stephen Hero, Joyce declared, “I am sure however that the whole structure of heroism is, and always was, a damned lie” (Ellmann, 192). He did not change this opinion. The hero of Ulysses is Leopold Bloom rather than Stephen Dedalus, but Bloom is decidedly an anti-hero by the standards of ancient Greek epic. Heroism of the type exemplified by athletes and warriors is subjected to ironic scrutiny throughout the book, and made utterly ridiculous in Cyclops.

x. Epi oinopa ponton ‘—’ snotgreen

xi. [mulligan’s] great searching eyes ‘—’ "mobile eyes”; "silver points of anxiety in his eyes."

xii. Malachi: Mulligan's determination to “Hellenise” Ireland arguably does make him a kind of prophet, albeit an anti-Christian one. This assumption is supported by the way Telemachus presents him as the bearer of evangelical "tidings": “He swept the mirror a half circle in the air to flash the tidings abroad in sunlight now radiant on the sea.” In Hart and Hayman's James Joyce's Ulysses, Bernard Benstock argues that the book makes Mulligan a kind of John the Baptist to Stephen’s Christ, in the very limited sense that he appears first, dramatically preparing the way for Stephen to emerge as a character shortly after. By this logic, Mulligan’s crudely anti-Christian message could perhaps be characterized as a proclamation of Good News that introduces Stephen’s similar but much more complex and nuanced message. ‘—’ Later in the chapter Mulligan calls himself "Mercurial Malachi" and the narrative refers to his Panama hat as a “Mercury’s hat,” alluding to the famous winged hat of the god Mercury. Since Mercury, the Romanized version of the Greek Hermes, was often represented as the gods' messenger, carrying decrees down from Mount Olympus to human beings on earth, this detail builds upon Mulligan’s Hebrew name of Malachi. ‘—’ Mulligan is clearly aware of the biblical significance of his name. In Scylla and Charybdis he borrows a scrap of paper on which to jot down an idea for a play: "May I? he said. The Lord has spoken to Malachi."

xiii. Mirrors (As others see us): “As he and others see me”: regarding himself in the mirror held up by Mulligan, Stephen recalls two well-known lines of the Scottish poet Robert Burns (1759-96). Burns wrote, "O wad some Power the giftie gie us / To see oursels as ithers see us!" The thoughts that follow in Telemachus ("Who chose this face for me? This dogsbody to rid of vermin") make clear that Stephen knows the whole poem and is thinking about its message: objective representation threatens subjective self-satisfaction, and the body humbles the mind. Bloom knows the poem too, and thinks about its crucial line in similar ways.

Burns' lines come from a poem titled On a Louse: On seeing one on a lady’s bonnet at church, and they cannot be properly appreciated without contemplating the scene that is vividly set out in the poem's opening stanzas:

Ha! Whare ye gaun, ye crowlin ferlie?

Your impudence protects you sairly,

I canna say but ye strut rarely

Owre gauze and lace,

Tho' faith! I fear ye dine but sparely

On sic a place.

Ye ugly, creepin, blastit wonner,

Detested, shunn'd by saunt an' sinner,

How daur ye set your fit upon her—

Sae fine a lady!

Gae somewhere else and seek your dinner

On some poor body.Such a sight was all too common in turn-of-the-century Dublin. Stephen will think later in this episode of his mother picking lice off her children and squishing them between her fingernails. The image recalls a similar event in A Portrait, and also another moment in that book in which Stephen snatches a louse from his neck and rolls it between his fingers. On the latter occasion, the thought of being louse-infested makes him doubt the value of his exquisite intelligence.

Burns pursues similar thoughts about how the body's infirmities can humble the mind's pretensions. The image of an ugly, creeping, blasted louse crawling over a respectable and presumably self-pleased lady leads him to his moral at the end of the poem:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us,

An' foolish notion:

What airs in dress an' gait wad lea'e us,

An' ev'n devotion!People are liberated, Burns asserts, by their ability to see themselves objectively—i.e., as objects, from the outside—because the reality of our existence never quite measures up to our flattering self-conceptions. Shortly after Stephen thinks of Burns while looking at himself in the mirror, Mulligan alludes to an Oscar Wilde saying about mirrors that has similar implications of unflattering self-knowledge.

In Lestrygonians, Bloom recalls Burns’ famous line as he watches men “wolfing gobfuls of sloppy food”: “Am I like that? See ourselves as others see us. Hungry man is an angry man.” Shortly later he associates it with a similar line from Hamlet, thinking, "Look on this picture then on that." At this moment in act 3 scene 4, Hamlet forces his mother to look at portraits of her first and second husbands. Just as Hamlet forces Gertrude to behold Claudius' ugliness and think about herself ("O Hamlet, speak no more: / Thou turn'st mine eyes into my very soul; / And there I see such black and grained spots / As will not leave their tinct"), Bloom beholds ugliness and wonders about himself.

He is still thinking along such lines in Nausicaa. When an unknown “nobleman” passes by on the beach after supper, Bloom imagines following him to observe what he is like: “Walk after him now make him awkward like those newsboys me today. Still you learn something. See ourselves as others see us. So long as women don’t mock what matter?”

II. Nestor

III. Proteus

IV. Calypso

V. Lotus Eaters

VI. Hades

VII. Aeolus

VIII. Lestrygonians

IX. Scylla and Charybdis

X. Wandering Rocks

XI. Sirens

XII. Cyclops

XIII. Nausicaa

XIV. Oxen of the Sun

XV. Circe

XVI. Eumaeus

XVII. Ithaca

XVIII. Penelope